Ceres History

Ceres History

Ceres

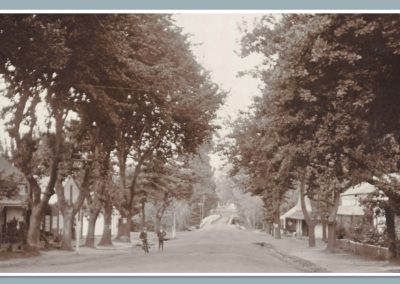

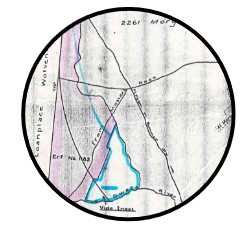

Stock farmers crossed the Witzen mountain range as early as 1727 to establish themselves in the “Koue” and “Warm Bokkeveld”. The accessibility of the area was greatly improved during 1848 when Andrew Geddes Bain built the Michells Pass and Fifteen of the properties was trasferred to the new owners on 29 October 1849. Thus was Ceres established on the 29th of October 1849.

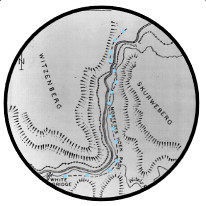

Mr. Michell was the Surveyor-General during that period and he was honoured with the pass bearing his name. The first erven were surveyed after the opening of the pass and the town Ceres, named after the Roman Goddess of Fertility (Fruitfulness) was officially given municipal status on 3 November 1864. The village of Ceres nestles between the picturesque Witzenberg and Skurweberg mountains.

The village of Ceres lies 140 kilometres to the North-East of Cape Town.

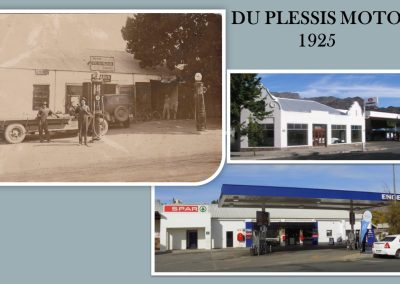

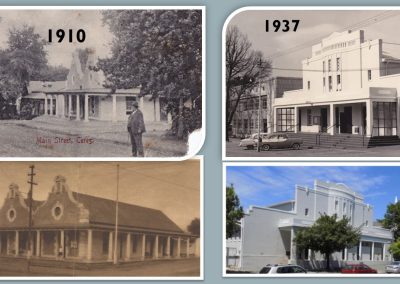

After the discovery of diamonds, the road through Ceres became the main route to Kimberley. Ceres was the last town to the north on this route and brought prosperity to the town. The prosperity was, however, short-lived when a railway line was constructed to the north via Wolseley in 1885.

In the subsequent development in Ceres the focus was turned to the development in local agriculture. The deciduous fruit production was boosted only after the completion of the railway line to Wolseley in 1912. (The railway line catered for goods only).

Since the establishment of the Deciduous Fruit Board in 1939 (controlling the packing, shipping and marketing of fruit in foreign countries) continuous growth was experienced in the deciduous trade and accompanying growth of the town.

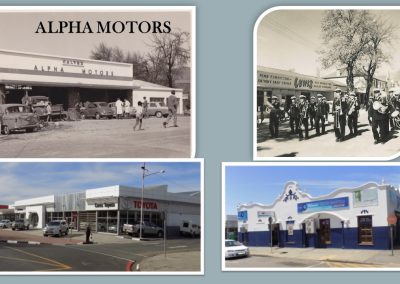

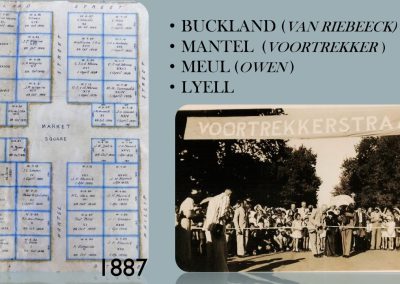

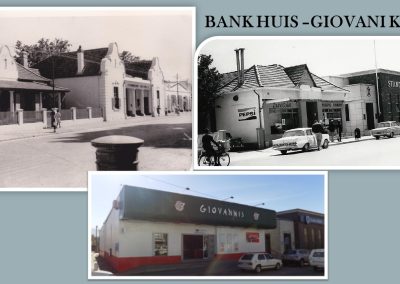

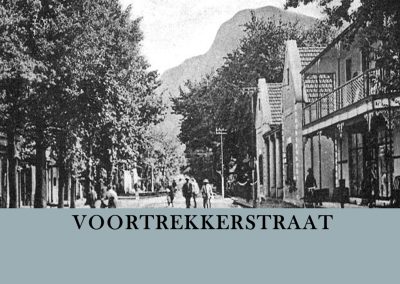

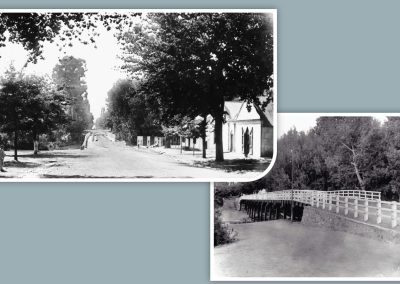

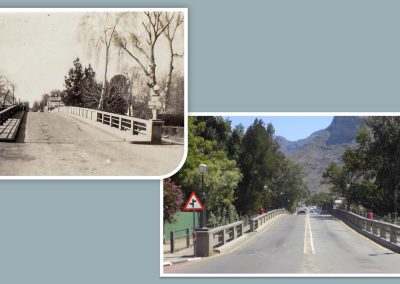

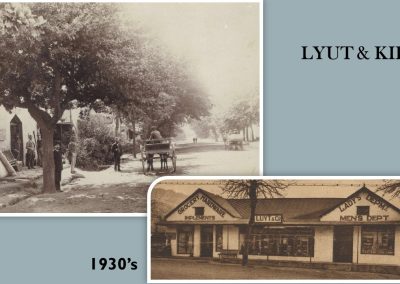

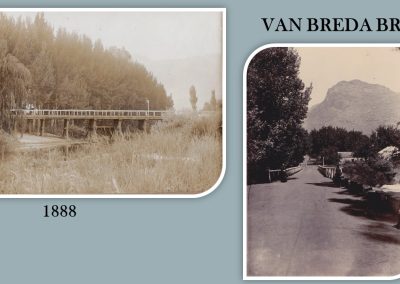

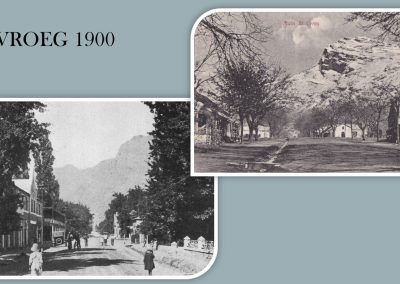

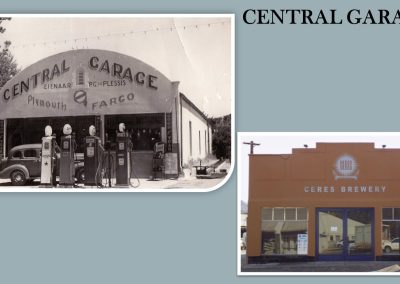

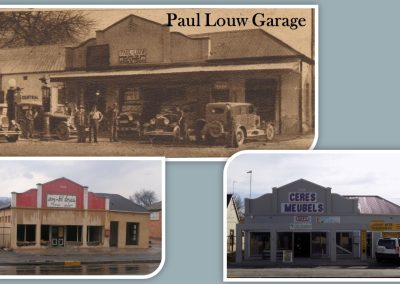

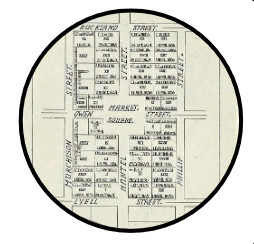

After the discovery of diamonds in Kimberley the main route through Ceres was Voortrekker Street. It was the only street in Ceres with bridge crossing over the Dwars River and businesses were naturally established on this route. Town development was originally made to the west of the river in and around Market Plain.

Farmers sold their produce on Market Plain and traded in this area with the result that the market became the main focus point in town.

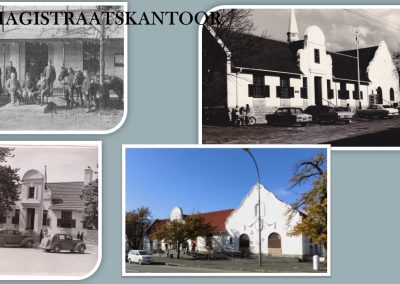

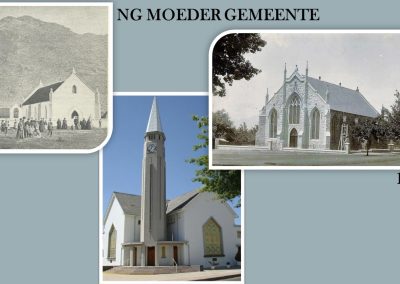

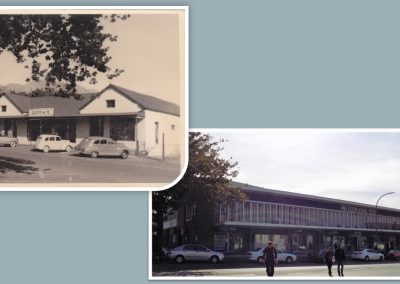

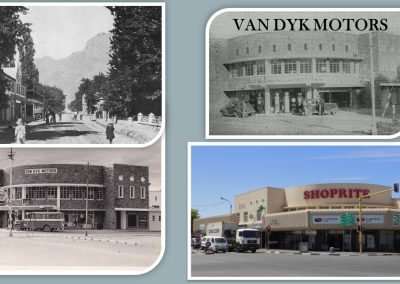

The market place changed character in recent years and can no longer be separately identified due to the coalescence with the roads. Public institutions presently border the market area, viz a church, magistrates office, post office and municipal offices. Business development took place in straight line fashion along Voortrekker Street. Due to the development of farming north of Ceres, the importance of the link road to the north put more emphasis on Vos Street.

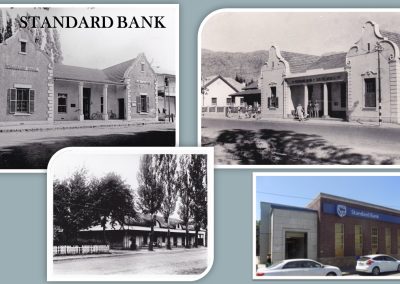

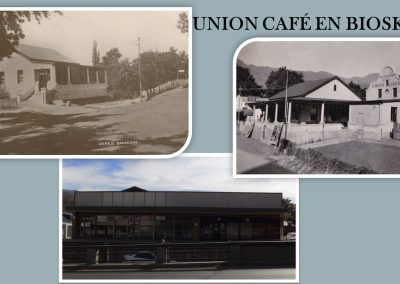

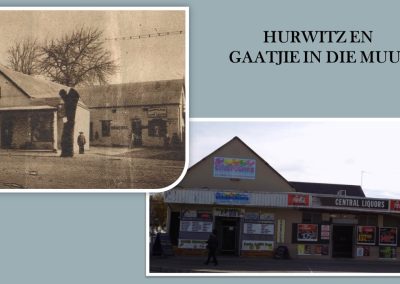

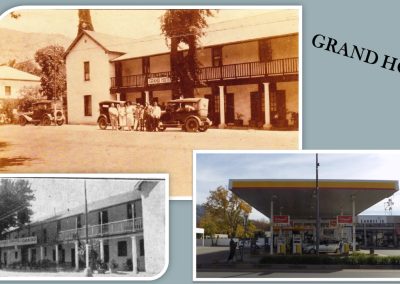

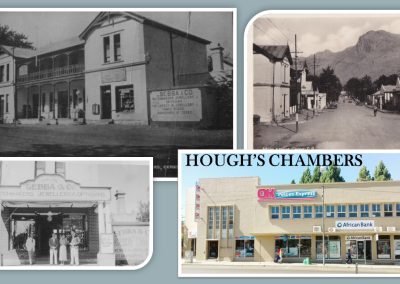

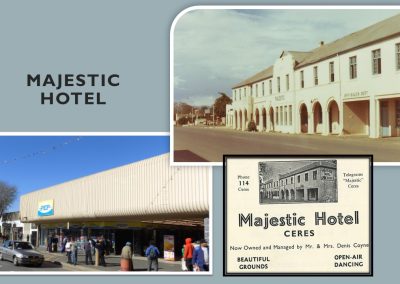

One characteristic feature of Ceres is the fact that dilapidated buildings do not exist which is a direct result of the earthquake that caused extensive damage to old buildings in town on 29 September 1969. Many old buildings were demolished after the earthquake.

The town was developed during a sterile architectural period with the result that no buildings could be classified as historic.

Ceres is one of the largest deciduous fruit and vegetable producing districts in South Africa. Fresh fruit is marketed both locally and internationally as are other products such as fruit juices, dried fruit , potatoes and unions. The first Ceres wines have recently appeared on the market and local spring water is sold worldwide.

The mountains are often snow-capped in winter and on several occasions the snowfall is low and heavy enough to be reached by visitors.

In the subsequent development in Ceres the focus was turned to the development in local agriculture. The deciduous fruit production was boosted only after the completion of the railway line to Wolseley in 1912. (The railway line catered for goods only.) Since the establishment of the Deciduous Fruit Board in 1939 (controlling the packing, shipping and marketing of fruit in foreign countries) continuous growth was experienced in the deciduous trade and accompanying growth of the town.

As a result of the prominent mountain range which forms a physical boundary between this area and the Cape Metropole, a strong service sector has developed locally. Agriculture and especially deciduous fruit and grapes form the economic basis of this region, with the result that the town has developed into a service centre for the farming communities.

Natural History

Topography

The geology, specifically the composition of the rocks and the large folded structures, have the greatest effect on the region’s topography. It can be safely assumed that the highest mountain ranges will be composed of hard sandstone and quartzites, while softer, faster weathering shales underlie the valleys. The large-scale folding defines the overall orientation of the mountain ranges. The north-south orientated Koue Bokkeveld and Skurweberg mountains correspond to north –south fold axes (mainly anticlines – see geology panel), and likewise for the east-west orientated Hex River Mountains. The flat lying geology of the Tanqua Karoo results in broad flat plains where there is softer rock and flat-topped mountains (buttes and mesas) where a harder rock formation forms a protective capping.

The highest peaks in the area are the Matroosberg (2270m?) and Sneeuwkop (2070m). These mountains are often snow-capped in winter and are great attractions to the “snow-mad” South Africans. The Koue Bokkeveld to the north of Ceres, is a higher lying area of between 500 and 1500 metres higher than the Warm Bokkeveld. The Warm Bokkeveld lies between 150 and 500 metres. The central plain of the Tanqua Karoo lies between ? and ? metres, with Skoorsteenberg and the Roggeveldberge forming the eastern boundary

Climate/Klimaat

The names, Warm Bokkeveld, the Koue (Afrikaans = cold) Bokkeveld and the Ceres or Tanqua Karoo (Khoi = thirst), already give one a hint of the diverse nature of the region’s climate 1. Weather is a complex phenomena we experience every day and many aspects can be measured including temperature 2, precipitation 3, humidity 4, evaporation 5 , air pressure 6, wind speed and wind direction.

The weather we experience is a result from temperatures difference between day and night (diurnal 7 fluctuation), the ocean and landmass (oceans tend to moderate temperature) and altitude (adiabatic lapse rate 8). An increase in air temperature results in an increase in volume and a corresponding decrease in air pressure. The result of differences in air temperature is atmospheric instability or “moving air” which we call wind. Winds can move vertically or horizontally. Air can rise either due to heat as thermals or be forced to rise on meeting obstacles such as high topography or other denser air masses. Once air rises it cools, condenses 9 to forms cloud which in turn can result in precipitation (drizzle, rain, hail or snow).

In the Ceres region the greatest factor affecting temperature and precipitation is altitude 10 and topography 11. The difference in altitude between the Warm Bokkeveld and the Koue Bokkeveld is roughly 500 metres or 5oC – thus the name “Cold” Bokkeveld. The change in air temperature is quite evident as one drives up Gydo Pass and is also shown graphically in the temperature graphs of Deelville (Warm Bokkeveld) versus Paardekloof (Witzenberg Valley Koue Bokkeveld) and De Keur (Koue Bokkeveld).

In winter, the cool, moisture laden westerly winds are forced to rise by the Skurweberg and Koue Bokkveld mountains from sea-level to more than 2000 metres. The topographic / rainfall map illustrates the relationship between topography and rainfall, this type of rainfall is called orographic 12,. The mountain ranges receive the highest rainfall (2100 – 800mm), while in the Koue Bokkeveld , the high lying plateau receives a moderate rainfall (800 – 300mm). The lower areas of Warm Bokkeveld (400 – 300mm) and the Tanqua Karoo (250 – 100mm) are found within the rain shadow and receive less rain. The rainfall increases over the Great Escarpment of the eastern Tanqua Karoo.

Glossary

- Climate – defined by scientists as the “integrated effect of weather typical of a site or region”.

- Temperature – the concentration of sensible heat in a body and measured on the Celcius and Kelvin scales.

- Precipitation –water droplets or ice particles large enough to fall at least 100m below the cloud base before evaporating (drizzle, hail, rain and snow).

- Humidity – the vapour content of air

- Evaporation – the effusion of water vapour from a water mass or body

- Air pressure – the mass of a column of air of unit cross section or the force acting on a unit area – pressure is measured in newtons per square metre or pascals, but also commonly in millibar of mercury.

- Diurnal – daily cycle

- Adiabatic lapse rate (dry) – a parcel of rising air will cool at a rate of 1oC per 100m, or will warm at the same rate on descent.

- Condensation – the growth of water or ice (sublimation) by diffusion from contiguous vapour.

- Altitude – height above sea level in metres

- Topography – landform

- Orographic rainfall – occurs as a result of relief of the ground

Geology

Rocks and fossils of the Ceres district

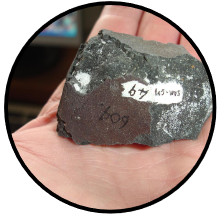

Two major sedimentary rock sequences are found in this region. The Cape Sequence consists of mostly sandstones and quartzites with minor shale formations, while the Karoo Sequence consists of mostly shales and siltstone with minor sandstone formations. The different rock types represent different palaeo-environments, with the coarser grained sandstones and quartzites deposited in higher energy environments such as beaches or rivers, while the the finer grained shales and siltstones are deposited in lower energy environments such as deep water lakes or seas. The depositional environment also plays a role in the preservation of fossils, i.e. fossils in low-energy environments have a greater chance of preservation than those in higher energy environments.

The Cape Sequence occurs mostly on the western half and southern side of the Ceres district. The sequence consists of, from oldest to youngest, the Peninsula Formation (equivalent to the quartzites forming Cape Town’s Table Mountain), the Pakhuis Formation (a glacial tillite), the Cederberg Formation (shales), the Nardouw Formation (sandstones and quartzites), the Bokkeveld Group (shales with bands of sandstone) and the Witteberg Group (sandstones with minor shale). The Cape Sequence was deposited between the Upper Ordovician (±450 Ma – million years) and the Lower Carboniferous (±354 Ma).

The Karoo Sequence is found mostly in the eastern half of the Ceres district and consists of the following formations: Dwyka Formation (glacial tillite), Prince Albert and White Hill Formations (siltstones and carbonaceous shale, chert bands), Ecca Group (Tierberg – siltstone and shale, Skoorsteenberg – sandstone, shale and siltstone, Koedoesberg – sandstone, Kookfontein – sandstone formations) and the Beaufort Adelaide Formation (sandstones). The Karoo rocks in the Ceres area are between 290 Ma (Upper Carboniferous) and 145 Ma years old (Jurassic Cretaceous boundary).

Fossils and other traces of life can be found in almost every rock formation, with the greatest concentration in the lowermost shales of the Bokkeveld Group (see marine brachiopods, trilobites and crinoids) and throughout the Beaufort Group (dinosaur reptiles and mammal-like reptiles). All fossils are protected by law and may not be disturbed or removed.

Folding and structure

One of the most striking features of the Ceres region is the high mountain ranges and Ceres is often referred to as the “Switzerland of South Africa”. These mountain ranges form part of a 1000 km mountain chain called the Cape Folded Belt. The mountain building is thought to be a result of continental tectonic plate movement, specifically South America colliding with Africa to form Gondwana. Some researchers, however, postulate that the folding is due to “soft sediment deformation”. The Cape folding event took place during the deposition of the lower Karoo sediments, i.e. between 300 Ma and 240 Ma. The only rocks of volcanic origin are the intrusive dolerite dykes (vertical) and sills (horizontal) of the Ceres Tanqua Karoo. The volcanic activity is related to the continental breakup of Gondwana, where India, Madagascar, Antarctica – Australia and South America broke away from Africa (about 145 Ma).

Very little deposition has occurred since the splitting up of Gondwana,, with the dominant process being weathering and erosion of the rocks to produce the present landscape.

Rocks and fossils of the Ceres district

Two major sedimentary rock sequences are found in this region. The Cape Sequence consists of mostly sandstones and quartzites with minor shale formations, while the Karoo Sequence consists of mostly shales and siltstone with minor sandstone formations. The different rock types represent different palaeo-environments, with the coarser grained sandstones and quartzites deposited in higher energy environments such as beaches or rivers, while the the finer grained shales and siltstones are deposited in lower energy environments such as deep water lakes or seas. The depositional environment also plays a role in the preservation of fossils, i.e. fossils in low-energy environments have a greater chance of preservation than those in higher energy environments.

The Cape Sequence occurs mostly on the western half and southern side of the Ceres district. The sequence consists of, from oldest to youngest, the Peninsula Formation (equivalent to the quartzites forming Cape Town’s Table Mountain), the Pakhuis Formation (a glacial tillite), the Cederberg Formation (shales), the Nardouw Formation (sandstones and quartzites), the Bokkeveld Group (shales with bands of sandstone) and the Witteberg Group (sandstones with minor shale). The Cape Sequence was deposited between the Upper Ordovician (±450 Ma – million years) and the Lower Carboniferous (±354 Ma).

The Karoo Sequence is found mostly in the eastern half of the Ceres district and consists of the following formations: Dwyka Formation (glacial tillite), Prince Albert and White Hill Formations (siltstones and carbonaceous shale, chert bands), Ecca Group (Tierberg – siltstone and shale, Skoorsteenberg – sandstone, shale and siltstone, Koedoesberg – sandstone, Kookfontein – sandstone formations) and the Beaufort Adelaide Formation (sandstones). The Karoo rocks in the Ceres area are between 290 Ma (Upper Carboniferous) and 145 Ma years old (Jurassic Cretaceous boundary).

Fossils and other traces of life can be found in almost every rock formation, with the greatest concentration in the lowermost shales of the Bokkeveld Group (see marine brachiopods, trilobites and crinoids) and throughout the Beaufort Group (dinosaur reptiles and mammal-like reptiles). All fossils are protected by law and may not be disturbed or removed.

Folding and structure

One of the most striking features of the Ceres region is the high mountain ranges and Ceres is often referred to as the “Switzerland of South Africa”. These mountain ranges form part of a 1000 km mountain chain called the Cape Folded Belt. The mountain building is thought to be a result of continental tectonic plate movement, specifically South America colliding with Africa to form Gondwana. Some researchers, however, postulate that the folding is due to “soft sediment deformation”. The Cape folding event took place during the deposition of the lower Karoo sediments, i.e. between 300 Ma and 240 Ma. The only rocks of volcanic origin are the intrusive dolerite dykes (vertical) and sills (horizontal) of the Ceres Tanqua Karoo. The volcanic activity is related to the continental breakup of Gondwana, where India, Madagascar, Antarctica – Australia and South America broke away from Africa (about 145 Ma).

Very little deposition has occurred since the splitting up of Gondwana,, with the dominant process being weathering and erosion of the rocks to produce the present landscape.

Fauna

Timeline

The loan farm Rietvallei is allocated to Willem van Heerden.

In 1854 Ceres would develop on a portion of the farm on the East Side of the Dwars River.

Jan Mostert built Mostershoek Pass.

Meteor fall in the Cold Bokkeveld.

Adrew Geddes Bain built Michell’s Pass.

The Pass was opened on 1 December 1848 and named after the then Surveyor-General of the Cape Colony, Conwell Michell.

Ceres was established in 1849 when the first 15 properties, part of 1800 acres of crown land, were transferred to the new owners on 29 October 1849.

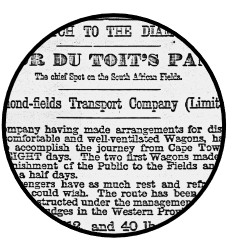

After the discovery of diamonds Ceres became one of the main stations on the diamond route to the north and the transport rider industry becomes very important.

The Diamond Fields Transport Company is established 4 Nov 1871.

This company introduced a weekly service between Cape Town and the Du Toit’s pan.

The directors were all residence of Ceres.

The “Belmont Sanatorium” was built in 1890 and was under the supervision of Dr. Gustav Zahn from England.

Ceres’ ideal for the treatment of pulmonary diseases

as well as for recuperation after serious illness.

Imperial Yeomanry arriving at Ceres.

The municipality was established on 3 November 1864 but only received full status on 18 November 1908.

The railway line reaches Ceres on 18 May 1912.

After the railway engineer failed to plot the required vertical and horizontal gradients through Michell’s Pass, Jan Keet, a local resident, measured the route for the railway line within three months.

Ceres Fruit Gowers Co operative Association Limited was registered on

Saturday, 13 January 1923.

On 21 November 1923 the Jewish Synagogue was inaugurated.

In May 1932 the first five tarred streets were completed.

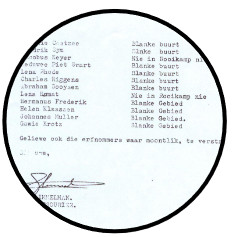

In an attempt to control the movement of black people in Ceres the Council set up a

temporary camp, Noodkamp, in 1940 (also later known as Sakkiesbaai.

The new Hydro-Electric Scheme was opened by the then Prime Minister J.G.

Strydom on 18 July 1953.

Ceres’ first hospital is inaugurated in

November 1955.

On 21 July 1962 the residence of Sakkiesbaai moved to Nduli due to the Group Areas Act of 195.

Residents of the Rooikamp were directly

influenced by the Group Areas Act.

The land on both sides of the southern end of Leyll Street, also known as ‘die Landjie’ by the local residents was one of the areas affected.

Residence were forced to moved away during 1965.

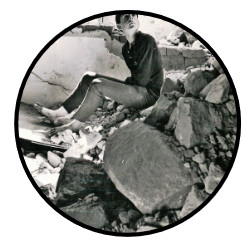

On 29 September 1969 the most destructive earthquake in the history

our South Africa struck the Boland area.

On 15 May 1999 the new Koekedouw Dam was inaugurated.

After the municipal election on 5 December 2000 Ceres is included in the

greater Witzenberg Municipality.

Flora

Ceres het ’n Mediterreense klimaat wat gekenmerk word deur warm, droë somers en koue, nat winters. Die hele distrik, wat die Koue Bokkeveld, die Warm Bokkeveld en die Ceres-Karoo insluit, val binne die winterreënstreek. Die jaarlikse reënval wissel tussen 1300mm in sommige bergklowe en 100mm in die droogste dele.

Die Koue Bokkeveld bestaan hoofsaaklik uit gronde van die Tafelberg¬sandsteengroep, die Warm Bokkeveld uit gronde van Bokkeveldskalie en die Ceres Karoo uit gronde van Dwykatilliet. Die hoogste bergpieke is meer as 2000m bo seevlak en die laagliggende dele in die Ceres Karoo is 500m bo seevlak. Hierdie en baie ander faktore het ’n invloed op Ceres se plantegroei. Daar word in die Ceres-distrik tussen hoofsaaklik drie plantegroeitipes onderskei naamlik, Bergfynbos in die Koue Bokkeveld, Renosterveld in die Warm Bokkeveld en Sukkulentkaroo in die Ceres-Karoo.

Bergfynbos is hoofsaaklik tot gronde van die Tafelbergsandsteengroep beperk. Dit is meestal goedgeloogde, onvrugbare grond. Bergfynbos word deur hoofsaaklik drie komponente gekenmerk naamlik, die besemriete (Restionaceae), die Proteafamilie (Proteaceae) wat hoofsaaklik breë blare besit waarvan die bo- en onderkant nie van mekaar ondeskei kan word nie en ’n heidekomponent, bestaande uit plante met meestal klein, smal, harde, omgerolde blare, wat nie slegs die heidefamilie (Ericaceae) insluit nie, maar ook lede van die madeliefiefamilie (Asreraceae), ertjiefamilie (Fabaceae), hardebosfamilie (Rhamnaceae), gonnatoufamilie (Thymelaeaceae), en die knoppiesbosfamilie (Bruniaceae).

Renosterveld is minder spesieryk as Bergfynbos en word gekenmerk deur die dominansie van lede van die madeliefiefamilie, veral renosterbos wat aan hierdie veldtipe sy naam gee. Meeste struike in Renosterveld het klein, leeragtige, grys blare en hierdie veldtipe is ook ryk aan geofiete (bolplante) van byvoorbeeld die irisfamilie (Iridaceae), katstertfamilie (Asphodelaceae) en die hiasintfamilie (Hyacinthaceae) terwyl die restio-, heide- en proteakomponent nie so goed verteenwoordig is nie. Grasse (Poaceae) kom ook volop voor.

Die plantegroei in Sukkulentkaroo word oorheers deur sukkulente dwergstruike waaronder die vygies (Mesembryanthemaceae) en plakkies (Crassulaceae) besonder opvallend is. Die madeliefies (Asteraceae) vorm ook ’n belangrike komponent van hierdie veldtipe terwyl die grasse, weens ’n gebrek aan somerreën, swak verteenwoordig is.

Sekere plante binne die onderskeie plantfamilies is nie tot ’n spesifieke veldtipe beperk nie, maar word dikwels in meer as een van hulle (veral in Bergfynbos en Renosterveld) aangetref, terwyl die Warm Bokkeveld aan die Weste-en Suidekant deur hoë bergreekse met Bergfynbos omring word en ook plante uit hierdie veldtipe tot sy geledere tel.

Ceres has a Mediterranean climate that is characterised by dry summers and cold wet winters. The whole district falls within the winter rainfall region. The annual rainfall varies between 1300mm in some mountain gorges to 100mm in the arid parts.

The Cold Bokkeveld consists mainly of soils of the Tafelberg sandstone group and the Warm Bokkeveld of soils of Bokkeveld shale, while the Ceres Karoo consists of soils of Dwyka tillite. The highest mountain peaks are more than 2000m above sea-level and the low-lying areas in die Ceres Karoo are 500m above sea-level. These and many other factors have an influence on the vegetation of Ceres. In the Ceres district a distinction is made mainly between three types of vegetation, namely Mountain fynbos in the Cold Bokkeveld, Renosterveld in the Warm Bokkeveld and Succulent Karoo in the Ceres Karoo.

Mountain fynbos is mainly limited to the soils of the Tafelberg sandstone group. This is mostly alkaline, nutrient poor land. Mountain fynbos is characterised by three components, namely the broom reeds (Restionaceae), the protea family (Proteaceae), which has mainly broad leaves, the texture of which is the same on top as underneath, and a heather component, consisting mostly of small, hard, curled-up leaves. The latter not only includes the heather family (Ericaceae), but also members of the daisy family (Asreraceae), pea family (Fabaceae), hardebossie family (Rhamnaceae), gonnatou family (Thymelaeaceae) and the knoppiesbossie family (Bruniaceae).

Renosterveld, which is also classed under the fynbos biome, has fewer species and is characterised by the dominance of members of the daisy family, particularly renosterbush from which the name of this veld type is derived. Most of the shrubs in the Renosterveld have small, leathery, grey leaves and this veld type is also rich in geophytes (bulbous plants) of, for example, the iris family (Iridaceae), katstert family (Asphodelaceae) and the hyacinth family (Hyacinthaceae), while the restio, heather and protea components are not as well-represented. Grasses (Poaceae) are also found in abundance.

The vegetation of the Succulent Karoo is dominated by succulent dwarf shrubs among which the vygies (Mesembryanthemaceae) and plakkies (Grassulaceae) are particularly conspicuous. The daisies (Asteraceae) also form an important component of this veld type while the grasses are poorly represented, owing to a lack of summer rains.

Certain plants in the various plant families are not limited to a specific veld type, but are often found in more than one of them (particularly in the mountain fynbos and Renosterveld), while the Warm Bokkeveld on the western and southern side is surrounded by high mountain ranges with Mountain fynbos where these plants are also found.

Rock Art

Rock Art / Rotskuns

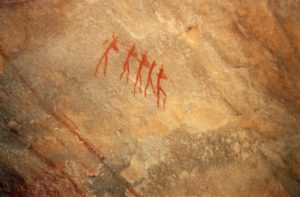

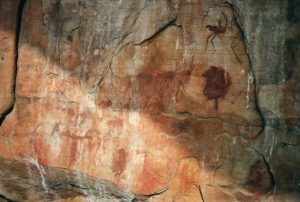

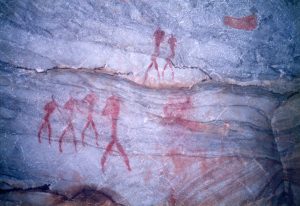

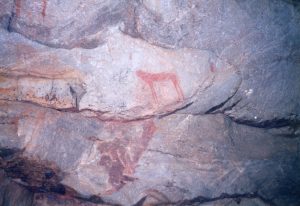

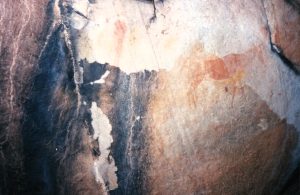

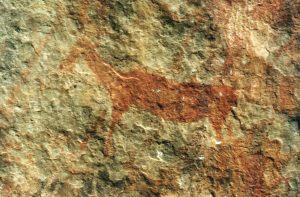

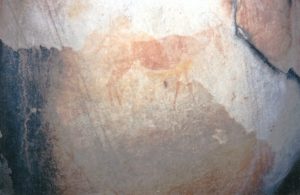

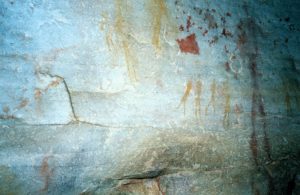

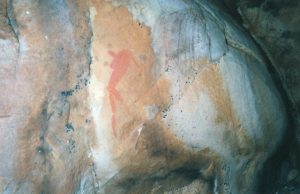

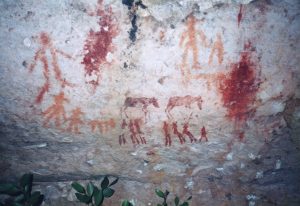

The Western Cape, particularly the mountainous region from the Cold Bokkeveld north through the Cederberg to the Agter Pakhuis area, may have more rock paintings per square kilometer than anywhere else in Southern Africa. In South Africa, rock art was made by San hunter-gatherers and Khoekhoen pastoralists. Black farmers created rock art of a different kind. Modern-day San living in the Kalahari do not produce rock art and practise a different culture from the southern San (/Xam) hunter-gatherers. The creation of images on rocks has an extraordinarily long tradition in Southern Africa and South Africa probably has the richest legacy of rock art in the world. The oldest scientifically dated work is in Southern Namibia and is estimated to be about 27 000 years old. In a few remote places in the Drakensberg, rock art was still being produced at the end of the 19th century.

The art consists of both paintings and engravings. Engravings are generally found in open-air sites in the interior of South Africa. The artists used several techniques, either pecking (stippling) or cutting lines in the patina known as fine line engravings. In contrast to the engravings, paintings are found in rock shelters and shallow overhangs.

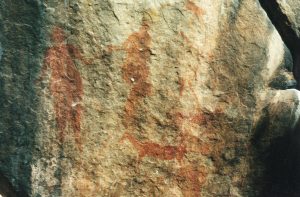

The materials used to make these paintings were generally different kinds of minerals. Red is the most commonly used colour and was made from ferric oxide and ochre of various shades. Black pigment was prepared from charcoal and specularite. White, the most ephemeral colour, was made from silica, china clay and gypsum. Other media used by the San include plant sap, eggwhite and perhaps water. The paint was applied with brushes made from reeds, feathers, quills or hair, or directly with the fingers. Fingerdots and handprints are found extensively in the Western Cape, Eastern Free State and the Eastern Cape.

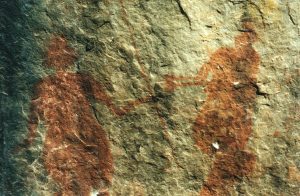

Southern African rock art essentially contains a religious element. San religion, like many others, used ritual practices to generate supernatural powers. The paintings and engravings recorded the experiences of shamans or medicine men and women in an altered state of conciousness (trance). They “became” animals in order to enhance their power as healers or rainmakers, or to control game during a hunt.

Trance was induced by dancing around a fire, singing and chanting repetitive songs, and hyperventilating. Men, women and children all took part either as dancers or by singing and clapping. In an altered state of consciousness, the shaman perceived images and believed he was part of those images. During the first stage of the trance the shaman saw patterns of light like grids, wavy lines, dots, vortices and zigzags. During the second stage, animals or objects of significance were seen; the eland being particularly important to the San. During the third stage of the trance all the images from the previous stages are merged. All of these experiences are depicted in San art and images of people with animal heads and hooves were frequently recorded.

The healing dance and the sensations experienced by the shaman when receiving potency are encoded in the posture of the human figure and other images. Paintings in the Western Cape and elsewhere in South Africa depict women clapping and people dancing in circles. People shown bending forward from the waist are depicted as experiencing “boiling energy”. Paintings also show people bleeding from the nose. Potency is represented by a line from the nape of the neck. Both tall, stretched-out figures and tiny figures were used to portray the sensations of the trance. People shown in a horizontal position depict shamans collapsed into unconsciousness. Birds and fish in the images portray the shamans’ sensations of feeling so light they could fly, or feeling as though they are under water.

Paintings and engravings sometimes depict animals as part of the rainmaking ritual, although the form of these animals varies. The most commonly depicted animal in San art is the eland. It is often depicted with a bleeding nose, a lowered neck and hair standing up on its neck. The portrayal of the dying animal is also a metaphor for the “dying” shaman. In the Cederberg and Warm Bokkeveld, paintings of elephants are common, reflecting perhaps their importance to that area. Other animals also frequently depicted in this area are rhebuck and hartebeest.

Die Wes-Kaap, en meer bepaald die bergagtige streek van die Koue Bokkeveld af noord deur die Sederberge tot by die Agter-Pakhuis-gebied, het meer rotstekeninge per vierkante meter as enige ander plek in Suidelike Afrika. In Suid-Afrika is rotstekeninge deur San jagter-versamelaars en Khoekhoen herders gemaak. Swart boere het rotskuns van ’n ander aard geskep. Die skep van beelde op rots het ’n besondere lang tradisie in Suidelike Afrika en Suid-Afrika het waarskynlik die rykste erfenis van rotskuns ter wêreld. Die oudste wetenskaplik gedateerde werk is in suidelike Namibië gevind en is om en by 27 000 jaar oud. Op ’n paar afgeleë plekke in die Drakensberge is rotskuns steeds teen die einde van die 19de eeu beoefen.

Die kuns bestaan uit sowel skilderwerk as graveerwerk. Laasgenoemde word oor die algemeen in opelug vindplase in die binneland van Suid-Afrika aangetref. Die kunstenaars het verskeie tegnieke gebruik – òf prikking (stippeling) òf die sny van lyne in die verweringslae op gesteentes, wat bekend staan as lyngravures. Anders as die graveerwerk word die skilderwerk in rotsskuilings en vlak oorhange aangetref.

Die materiale wat gebruik is om hierdie tekeninge te maak, het oor die algemeen uit verskillende soorte minerale bestaan. Rooi is die kleur wat die meeste gebruik is en is gemaak van ferrioksied en verskillende skakerings van oker. Swart pigment is berei van steenkool en spekulariet. Wit (die kleur wat die maklikste verweer) is gemaak van silika, porseleinklei en gips. Ander bestanddele wat moontlik as bindmiddels deur die San gebruik is, is onder andere plantsappe, eierwit en water. Die verf is aangebring met kwaste van riet, vere, slagpenne en hare, of direk met die vingers. Vingerafdrukke en handafdrukke word uitgebreid in die Wes-Kaap, Oos-Vrystaat en die Oos-Kaap aangetref.

Suid-Afrikaanse rotskuns bevat in wese ’n godsdienstige element. San godsdiens, soos baie ander, het rituele gebruik om bonatuurlike kragte te genereer. Die skilderwerk en graveerwerk het die ervarings van sjamane of toordokters in ’n toestand van beswyming aangetoon. Hulle het diere “geword” ten einde hul krag as genesers en reënmakers te versterk of om wild tydens ’n jagtog te beheer.

’n Beswyming is teweeggebring deur dansery rondom ’n vuur, die sing van herhalende liedjies, en hiperventilering. Mans, vrouens en kinders het almal deelgeneem – as dansers of deur te sing en hande te klap. Tydens so ’n beswyming het die sjamaan beelde waargeneem en geglo dat hy deel daarvan was. In die eerste stadium van die beswyming het die sjamaan ligpatrone gesien soos roosters, golwende lyne, spikkels, spirale en sigsagpatrone. Tydens die tweede stadium is diere of betekenisvolle voorwerpe gesien; veral die eland was van besondere belang vir die San. In die derde stadium van die beswyming het al die beelde van die vorige stadiums saamgesmelt. Al hierdie ondervindings word weergegee in San kuns en beelde van mense met dierkoppe en –hoewe (theriantropiese figure) is dikwels aangetref.

Die helingsdans en die sensasies wat die sjamaan ondervind het wanneer hy krag ontvang het, word in die postuur van die menslike figuur en ander beelde vergestalt. Skilderkuns in die Wes-Kaap en op ander plekke in Suid-Afrika beeld vrouens uit wat hande klap en mense wat in sirkels dans sowel as mense wat vooroor buig vanuit die middellyf. Ook mense met neusbloeding kom daarop voor. Kragtigheid word verteenwoordig deur ’n lyn vanuit die nekholte. Lang sowel as uitgestrekte figure en klein figure is gebruik om die sensasies van die beswyming uit te beeld. Mense in ’n horisontale posisies beeld sjamane uit wat ineengestort het in ’n toestand van beswusteloosheid. Voëls en visse in die beelde beeld die sjamane se sensasies uit van so lig te voel dat hulle sou kon vlieg, of onder water verkeer.

Die tekeninge en graverings beeld soms diere uit as deel van die reënmaakritueel, alhoewel die voorkoms van hierdie diere verskil. Die dier wat die algemeenste in San uitbeeldings voorkom, is die eland. Dit word dikwels met ’n bloeiende snoet, afwaarts geboë nek en regopstaande nekhare uitgebeeld. Die skets van die sterwende dier is ook ’n metafoor van die “sterwende” sjamaan. In die Sederberge en Warm Bokkeveld is skilderye van olifante algemeen, wat miskien hul belangrikheid in daardie omgewing weergee. Ander diere wat ook dikwels in hierdie gebied uitgebeeld is, is die ribbok en hartebees.